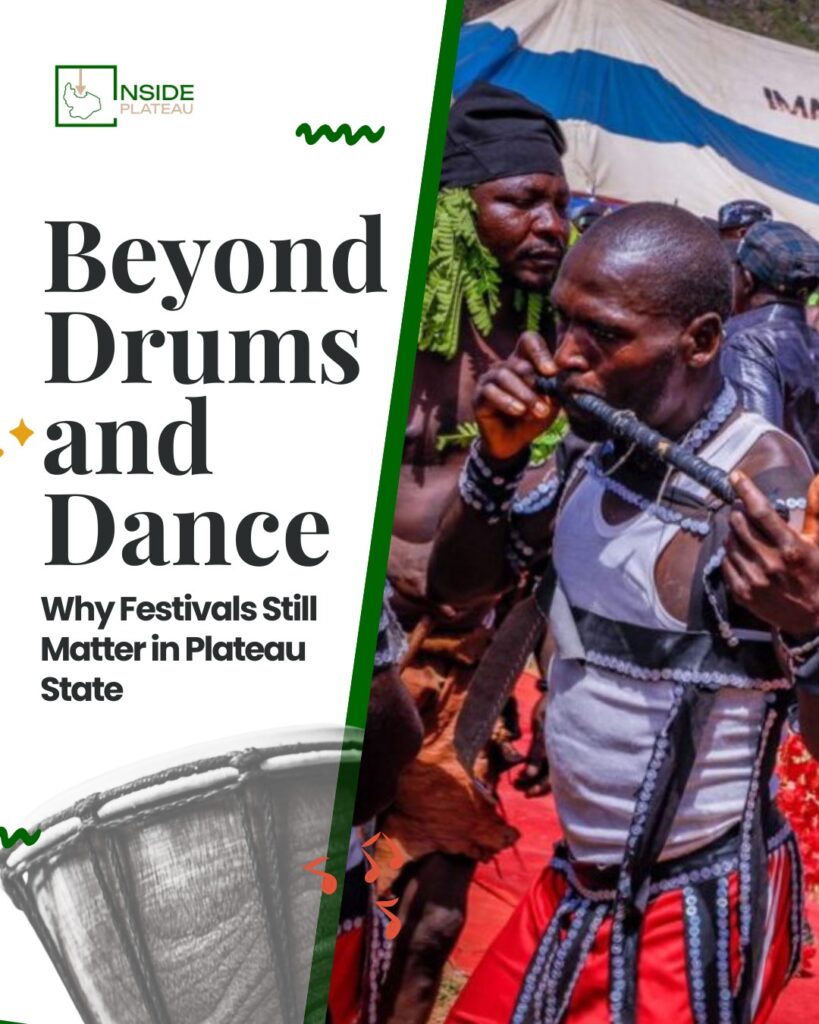

The drums are preparing to return as the harmattan takes shape in anticipation of the rainy months ahead. It is within this season that communities across Plateau State begin to prepare for their array of festivities. From Jos to Langtang, Bassa to Barkin Ladi, festival dates are being marked quietly on calendars, costumes are dusted off, cultural troupes begin rehearsals, while elders talk and the youth anticipate.

In the coming months, celebrations like Nzem Berom, Igoon‑Izere, Puus Kaat, and other community festivals will once again draw crowds, filling village squares and city centres with colour, rhythm and excitement.

For many, these moments are familiar, beautiful, and expected. However, long before stages, microphones and tourism calendars, Plateau festivals were never created for entertainment. They were inventions of survival.

ALSO READ: How Plateau state Diaspora Is Giving Back: Jos to the World

A Land That Needed Rituals to Live

Centuries ago, the Plateau was a very different place. There were no weather forecasts, no fertilisers, no irrigation system, and no structured markets. Communities lived close to the land, and the land decided everything. When the rains delayed, hunger followed. When hunting failed, families went without meat for months. When conflict lingered, entire settlements fractured.

In that world, festivals were not leisure. They were systems, carefully designed gatherings that helped communities manage fear, faith, food and fellowship. Each festival emerged because something essential needed explaining, protecting or sustaining.

To understand why these celebrations still matter today, we must first step backward, and stand quietly inside the moments that created them.

When Rain Decided Life: Mandyeng of the Berom

In those days, before calendars and forecasts, time was not counted by months, days or even hours. It was counted by rain.

The dry season had lingered too long, hence, across Berom land, grasses cracked beneath harmattan winds, streams shrank into narrow veins, hunting paths grew quiet, and seed barns stood ready, yet untouched. No one tilled the soil because it was forbidden. Farming could not begin until Mandyeng had spoken. So the elders converged.

They came from hamlets scattered across the hills—Dagwoms (district heads), Bedamajei (village leaders), and custodians of clans whose authority rested not in crowns but in memory. Each carried stories older than the stones beneath them, and they each knew that their decision would shape the year ahead.

So, they gathered at the ritual ground, near Nott or Kwit (a space reserved for moments that concerned the entire people). No drums announced the meeting, neither was there any dancing to soften the mood.

At the centre of this gathering lay symbols of continuity: old ashes from the previous year’s fire, calabashes of local brew, hunting horns placed gently on the earth. The order was simple: the fire burning in every home across the Berom land would soon be extinguished in unison, but not yet. Before any ritual is conducted, reconciliation must first preceed.

For this reason, disputes were called forward: boundary quarrels, unpaid bride prices, broken promises between families were all to be resolved completely. This was because Mandyeng could not proceed with unresolved anger. The belief was firm that a divided people could not ask the land for abundance. Hence, forgiveness was not sentimental, but a necessity.

Only after grievances were settled did the chief priest rise—the one entrusted to speak on behalf of the living to Dagwi (the Father of the Sun, supreme over all things). Among the Berom people, there were no masquerades, no spirit-manifests, only Dagwi and the ancestors (Vu Vwel), who served not as gods, but as messengers between worlds.

Now, libation followed as locally brewed beer was poured gently into the earth, not in worship, but in remembrance. This simple action served as gratitude for the year that had passed, pleas for the year approaching, and prayers for rain, for children, for peace, for animals in the bush, as well as for wars not to come.

Then came the fire. Across Berom land, old flames were extinguished, hearths went dark at the same hour. Consequently, at the ritual grove, two dry sticks were rubbed together until smoke appeared, then flame, and a new fire for the people. The symbol of a new year. From this fire, households would later rekindle their own as a powerful declaration that the community moved forward together.

Only after this could the celebration begin. Now, Mandyeng unfolded over days. Preparations followed for food, costumes, instruments, and dances. With the rain invited to the land, hunters could once again embark on expeditions, youths could now prepare for courtship, families planned marriages, knowing that brides added strength to the farms once planting began.

As the music finally filled the air, they weren’t produced by drums, but breath. The Juu pipes sang in interlocking patterns, each tone meaningless alone, but complete only in unity. Similarly, horns echoed across the hills, ankle rattles marked rhythm, and dancers moved in square formations with men in front, women behind, reenacting order, balance, and continuity.

And when the final rites were done, instruments were packed away, because pleasure had its season and work awaited. Now, the earth was ready and so were the people. The rains could now come.

ALSO READ: The Ngaspiano: Plateau Music Putting Us on the Global Map

Why These Festivals Mattered Then

In a land marked by diverse cultures and festivities, the history of the Berom’s Mandyeng celebration is only one story among many. Across Plateau State, various communities were inventing similar gatherings for the same reason: life was fragile, and order had to be maintained.

In those days, festivals became the rhythm by which society breathed.

They marked time when there were no calendars. The land itself was the clock as fstivals announced when hunting could begin, when farming must wait, when marriage was permitted, and when rest was allowed. Without them, seasons blurred into uncertainty.

They also held communities together. These festivals were among the few moments when entire settlements gathered in one place, not as families or clans, but as one people. Decisions made during these periods carried weight because everyone was present. Elders mediated disputes, thereby, resolving long-standing grievances. Similarly, peace was restored not by punishment, but by consensus. In societies without formal courts or police, these festivals became justice.

Furthermore, these festivals also served as instruments of survival. Through shared rituals, people synchronized labour and resources, ensuring that food was redistributed. In so doing, young men learned discipline, young women learned responsibility, while children absorbed history long before they could read, through songs, movement, and repetition.

In this light, we could say that these festivals taught without classrooms; because every dance recalled an event, every rhythm echoed an origin story. When elders aged and voices weakened, the festivals carried their stories forward and what could not be written was danced; what could not be recorded was sung.

And perhaps most importantly, festivals reminded people that survival was collective. Because, in those days, no one farmed alone, no one hunted alone, neither did anyone pray alone. Whether invoking rain, thanking the land, or ushering in a new season, these celebrations reinforced a single truth: that the community stood or fell together.

Hence, in a society and at a time shaped by uncertainty, droughts, diseases, conflicts, and migration, festivals were not luxuries. They were anchors.

When the Old Ways Began to Fade

By the late 20th century, change arrived quickly. Christianity and Islam reshaped spiritual practice and western education altered priorities. Soon, urban migration scattered communities as the younger generations moved farther away from ancestral villages.

Gradually, many local festivals began to fade. Not because they lacked meaning, but because society had changed. Some rituals were no longer understood. Others conflicted with new beliefs. Village‑based celebrations struggled to survive in an increasingly modern Plateau and the drums grew quieter.

The Reinvention: When Many Became One

It was from this fear of cultural disappearance that a new idea emerged. In 1981, cultural leaders under the Berom Educational and Cultural Organisation (BECO) took a deliberate step: they merged several fading Berom festivals, including Mandyeng, Nshok and Badu into one unified celebration. Thus, Nzem Berom was born.

The goal was not convenience, but preservation. Rather than losing many festivals slowly, they created one strong platform capable of surviving modernity. One gathering large enough to educate youth, unify communities and project identity confidently into the future.

This act of convergence marked a turning point, converting festivals from ritual to representation, and sacred ground to shared ground. Similarly, across Plateau State, similar transformations occurred as what once lived strictly in village squares began appearing on public stages. Spiritual urgency softened into symbolism and ancient rituals evolved into cultural expression.

This was not a loss, but adaptation. Culture, after all, survives not by resisting time but by learning to walk with it.

ALSO READ: Cultural Renaissance in Plateau State: Plateau’s Return to Heritage Pride

Why Festivals Still Matter Today

In today’s Plateau, festivals serve new but equally vital roles.

Paramountly, they continue to serve as vessels of memory in a rapidly moving world. Where ancestors once gathered to preserve knowledge through repetition and ritual, today’s celebrations still perform that same task of teaching origin through experience rather than instruction.

In dress, language, procession and rhythm, young people encounter history not as abstraction, but as inheritance. What was once taught beside the hearth is now carried in public squares, yet the intention remains unchanged: that identity must be remembered before it can be sustained.

Today’s festivals also echo the ancestral pursuit of unity. Just as earlier festivals drew scattered settlements together to settle disputes and restore balance, modern celebrations create neutral spaces where difference yields temporarily to belonging. In these moments, culture becomes common ground. Music, movement and ceremony dissolve boundaries of ethnicity and belief, reaffirming what the elders long understood: that harmony within the community is as vital as harmony with the land.

Economically, festivals continue the ancient logic of shared prosperity. Where earlier gatherings facilitated barter, redistribution and collective labour, present-day festivals now energise entire local economies. Artisans craft regalia, farmers supply produce, food vendors trade, performers earn, transporters move crowds, hotels fill rooms. The mechanisms have modernised, but the principle remains familiar: when the people gather, livelihoods circulate. Culture, once again, feeds the community.

Perhaps most quietly, and most powerfully still, is that modern Plateau cultural festivals retain their healing role. While in the past, ritual gatherings reconciled broken relationships before planting could begin, today, they offer similar restoration in a land shaped by memory and loss. Festivals allow communities to assemble without reopening wounds, to share space without rehearsal of pain. In celebration, the people remember how to coexist. In continuity, they honour the ancestors’ wisdom that survival is not only physical, but social.

Beyond Drums and Dance

When the drums sound again this season, they are not merely calling people to dance. They are calling memory. They echo the footsteps of farmers who prayed for rain, hunters who carried villages on their shoulders, and elders who feared that silence would one day replace song.

Long before Plateau became a state, long before Nigeria became a nation, these rhythms already spoke, and to celebrate them today is not nostalgia. It is continuity. Because beyond the drums and dance lies something deeper: a people refusing to forget who they have been, so they may better understand who they are and who they must continue to be.