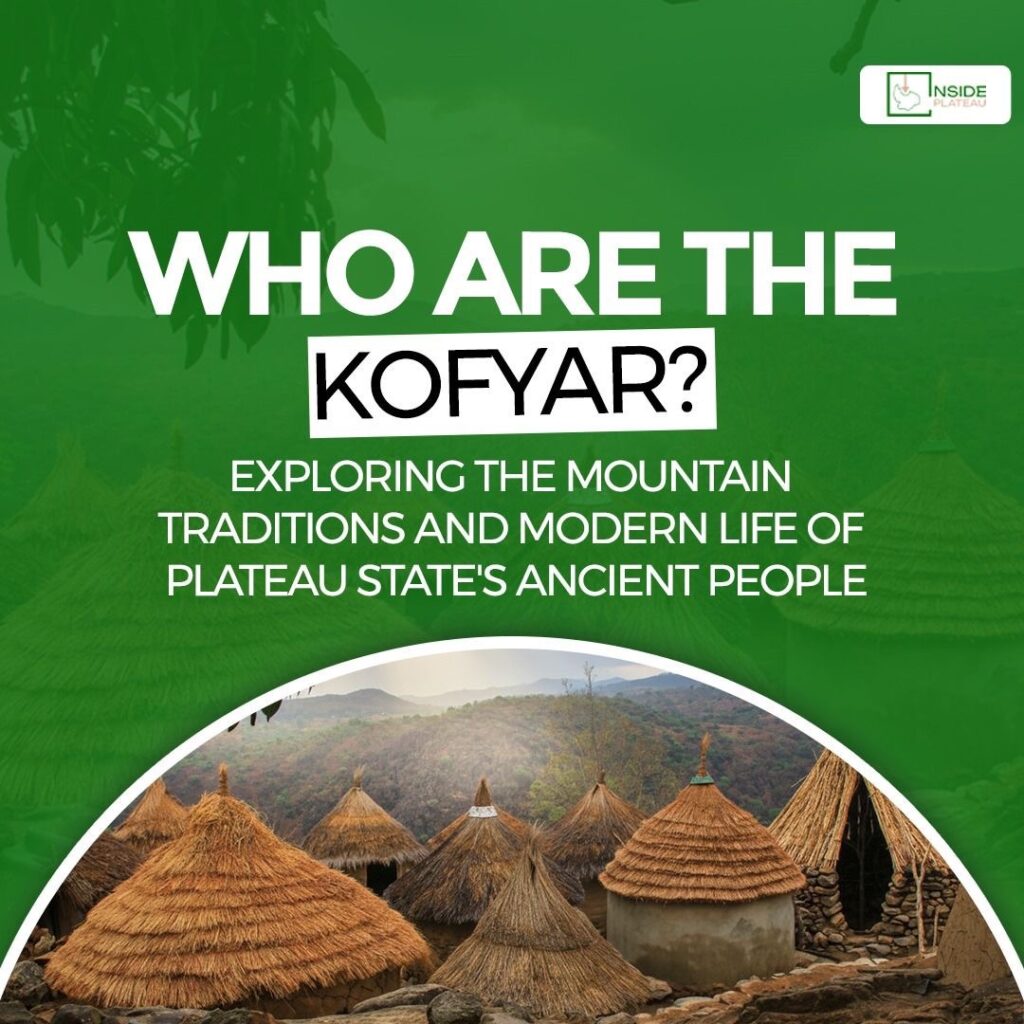

Tested on the Hills

When was the last time you climbed a mountain? Perhaps it was for the view, a hike with friends, or a weekend adventure. You probably packed a backpack holding water, snacks, maybe even a camera. Now imagine climbing not for fun, but for destiny. No food, no bag, no company. Just you, the rugged rocks, the silent night sky, and a people waiting to see if you’ll return alive.

This was the path of a Kofyar chief.

For the Kofyar of Plateau State, leadership wasn’t decided by posters or politics. It wasn’t a matter of who spoke the loudest, or who had the deepest pockets. To wear the crown, a man had to climb literally. Before his installation, he would spend seven days alone on a sacred mountain in Namu, Qua’an Pan. No feast was prepared for him. No servants followed him. The people believed that if he was truly chosen, the gods themselves would feed him with honey, with food, with life. His survival wasn’t luck. It was proof.

Now picture it: the second day, hunger gnaws at him. His throat is dry, his body weak. Doubt whispers in the wind. Then, almost miraculously, he stumbles upon nourishment. He eats, and strength returns. He survives. When he descends from the mountain after seven days, he is not the same man who climbed. He is reborn, marked by the gods, ready to lead. His people look at him differently now; not just as a man, but as a chief whose legitimacy is sealed in the unseen.

That story alone could stand as myth, but for the Kofyar it was lived reality. And it tells you everything you need to know about them: a people who see leadership as sacred, resilience as identity, and survival as proof of destiny.

From Rock to Root

To understand the Kofyar, you must first imagine their homeland. On the southern edge of Plateau State, in Qua’an Pan, lies a landscape carved by time and hands. Hills rise sharply, some scarred by old volcanoes. Between them, you find stone terraces that once turned impossible slopes into farmland. Ancient settlements still carry circular stone houses, animal pens built with dry stone, and even pyramidal graves where ancestors rest.

Anthropologists call it a megalithic living tradition. In simpler words: a civilization that built with stone, fortified with stone, and survived on stone. While other parts of the world let such traditions vanish, the Kofyar kept theirs alive for centuries. Even today, some of those stone structures still stand as silent witnesses to the ingenuity of a people who refused to bow to harsh terrain.

But don’t mistake the Kofyar for relics of the past. They have always been adapters. In the 1950s, many moved from their rocky hills to the fertile plains of the Benue Valley. There, they turned slash-and-burn farming into something remarkable: sustainable, market-oriented agriculture. Yams, rice, millet, sorghum, their farms began to feed not just themselves but entire markets. Anthropologists studied them as proof that African farmers, without big machines or foreign aid, could create systems both productive and sustainable.

It’s no exaggeration to say that the same resilience that once carried a chief through seven days on the mountain is the same resilience that carries the Kofyar through farming, migration, and modernization.

Who Are the Kofyar Today?

Ask around Plateau State and you’ll hear different names: Doemak, Kwalla, Mernyang, Bwall. These are the four main sub-groups of the Kofyar, all speaking dialects of the Pan language. Walk through Namu or Doemak and you’ll hear it in greetings, songs, jokes shared in the marketplace. It’s part of who they are one language, many voices.

Religion, too, has shifted. Once, the Kofyar’s spiritual world revolved around Moewoeng (or Moekwarkum), a supreme being who split existence into good and evil. Priests, diviners, and oracles stood as bridges between man and god, ancestor and living. Today, Christianity dominates. Churches dot the landscape, hymns mix with drums, and only a small number still keep traditional practices. Yet echoes remain: festivals, initiation rites, and sacred beliefs still weave through Christian practice, sometimes quietly, sometimes boldly.

And yes, the villages have changed. While many still hold on to the old stone walls and terraces as heritage, there are those who walk through Shendam or the Benue plains and live in concrete homes, send their children to school, work as teachers, business owners, engineers, and civil servants. Modernity has not erased them but expanded them. They are farmers, hunters, entrepreneurs, scholars. They are Plateau sons and daughters, rooted yet global.

So how would you know if you’ve met a Kofyar man or woman? By the pride. Ask them where they’re from, and they’ll tell you: from the hills, from the stones, from the people who made chiefs climb mountains.

Festivals That Breathe

Culture isn’t just what you inherit; it is what you celebrate; and for the Kofyar, festivals are where memory comes alive.

Ka Pang Mat Long (Mountain Climbing Festival): Every year in Namu, the climb still happens; not for chiefs alone, but for everyone. Before anyone ascends, they carry a prayer in their hearts: a job, a child, a healing, a hope. To climb is to petition the ancestors. It is both tradition and testimony.

Koes (Wrestling): December belongs to wrestling. Villages gather, drums beat, young men lock arms and test their strength. It is more than a sport, it is honor. Whoever wins is celebrated across Kofyar land.

Feer (Horn Music): Horns sound during coronations, funerals, or heroic celebrations. Imagine a wall of sound, deep and raw, rising with chants and drums. It is music that doesn’t just entertain, a summoning of memory.

Social Dances (Gya Gaa, Gay Dajhang): Circles form, drums at the center, men and women chanting, shuffling in rhythm. If you’ve ever lost yourself in a beat, you would understand: it is not about steps, but about belonging.

Through these festivals, the Kofyar prove that culture is not a dead history but a living fire.

What the Mountain Still Teaches

The story of the chief on the mountain is not just about the past; it’s a mirror. It tells you that leadership is sacred, not casual. It tells you that survival is never just individual, because when the chief climbs, he carries his people with him. It tells you that culture, like a man on a mountain, survives only when it refuses to quit.

Today, the Kofyar are found in their ancestral hills of Qua’anPan Plateau State, as well as in the Benue Valley (where many have moved for productive farmland), and portions of Nasarawa State. Some individuals also reside in cities beyond their homeland, though their central cultural stronghold remains in the Plateau. Many live in modern houses, speak English as easily as Pan, and work jobs their ancestors couldn’t have imagined. Yet the mountain remains. Some traditions are symbolic now, some are remembered only in festivals, but they all whisper the same truth: this is who we are.

So the next time you see a mountain on Plateau soil, think of the Kofyar. Think of a man walking up alone, empty-handed, hungry and returning after seven days as chief. Think of stone houses still clinging to the hills, farmers carving terraces into slopes, dancers circling drums, wrestlers locking arms in December dust. Think of a people who refused to let their culture vanish, who carried it uphill and still carry it now.

Because the Kofyar story is not just theirs. It’s a reminder to us all: culture survives when people continue to reach for it.