A People Rooted in Story

The Berom occupy Jos North, Jos South, Barkin Ladi, and Riyom, shaping nearly half the state’s identity. Their ancestry traces back to the Bantu migrations, but their story is written in Plateau’s soil. Farming and hunting were more than survival they defined who they were. Rituals like Mandyeng, which called the rains, and Nshok, which blessed the hunt, gave meaning to the cycle of seasons.

Hunting, especially, left its imprint in surprising places. Many Berom names from the past are animal names Tok, But, Kanyang. A child might be named after the quarry his father pursued, or an animal admired for its strength or cunning. Think about that for a moment: What if the name you have spoken casually for years actually carries the echo of a hunter’s story, a father’s pride, or a prayer for resilience? Suddenly, the name is no longer ordinary it is heritage in disguise.

Change and Resilience

Yet culture never stands still. Colonialism arrived with tin mining, pulling men from farms and shrines into shafts and offices. Christian missions shifted worship away from rivers and groves once believed to house spirits. In that moment, Berom rituals could have scattered into silence. Instead, they adapted. The many festivals of old were gathered under one banner Nzem Berom. What was once a ritual to spirits became, and still is, a ritual of remembrance. Every April, when the festival drums sound, it is both a celebration and a quiet act of defiance against erasure.

Iron and the Shift of Labor

Before the mines, the Berom were masters of iron. Blacksmiths smelted ore into tools and weapons, anchoring self-sufficiency. But colonial policies prized labor over tradition. Young men were encouraged sometimes forced into the mines, abandoning smelting, pottery, and weaving. The forges cooled, the craft declined. Pause here and imagine: what does it mean when a people who once created the tools of their own survival now work for wages dictated by outsiders? The story of iron is not just about a lost skill; it is about a people pushed into a new rhythm of life, one that still shapes Plateau today.

When Dance Speaks

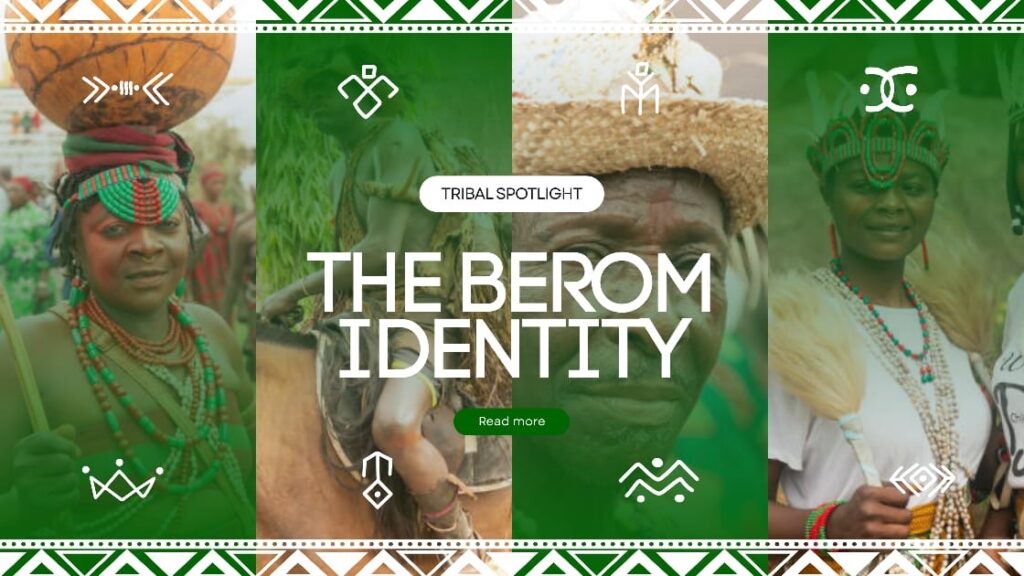

Berom dances are not mere performances; they are living poems in motion. Dancers leap as though vaulting the Plateau’s rocky heights, spin in arcs that sweep the crowd into rhythm, and punctuate each step with gestures that speak without words. A bowed back recalls the farmer planting, while a sharp turn mirrors the hunter’s pursuit. Faces, alive with expression, layer meaning into every movement.

Fashion Beyond Aesthetics

Then there are the costumes once woven from three symbolic colors: white, maroon, and dark green. Each carried its own story.

White, long central to Berom attire, represented peace and hospitality the very qualities for which the Berom were known. It also echoed the cactus plant, abundant across the Plateau, whose milky sap was both protective and useful. Wearing white was a way of saying: we are people of harmony, rooted in the land. But over time, as the culture evolved, white was removed from the official palette. Under the reign of Gbong Gwom Jos Da Victor Pam, the traditional council abolished its use to avoid cultural overlap with neighboring groups, like the Atyap, who also claimed white. Yet even now, you may spot Berom fabrics with traces of white sometimes as a fashion choice, sometimes as a quiet nod to heritage that refuses to be erased.

Maroon remains the most striking. It symbolizes ‘Tee’, the sacred powder that warriors once rubbed on their bodies for protection, healers used in medicine, and families trusted as a shield against evil. To see maroon in Berom attire is to glimpse centuries of belief in a substance that was at once physical, spiritual, and communal. Authentic tee still carries weight, though fakes circulate today, weakening its potency in practice but not in memory. Maroon is more than a color it is a reminder of the Berom’s enduring relationship with power, healing, and protection.

Dark green completes the palette. It embodies the spirit of agriculture the farms, the fertile soil, and the cactus fences that protect homesteads. For the Berom, whose survival has always been tied to the land, green is life. It is fertility, growth, and resilience. Each strip of dark green fabric proclaims the community’s identity as cultivators and stewards of the earth.

Together, maroon and green remain the official colors, stitched into wrappers, robes, and headscarves. During festivals like Nzem Berom, these colors do more than beautify the dancers they declare identity. They are memory made visible, a language as legible as the leaps and turns of the dance itself.

Custodians of Identity

Culture survives not only in festivals but through leadership. In 1935, the stool of the Gbong Gwom Jos was created, giving the Berom a central authority. From Da Dachung Gyang to the long reign of Da Rwang Pam, through Da Fom Bot, and now Da Jacob Gyang Buba, these rulers have been more than figures in regalia. They have been bridges protecting tradition while guiding their people through change. When you see the Gbong Gwom preside over Nzem Berom, you are not simply watching a leader at a festival; you are seeing continuity embodied.

Clearing the Misconceptions

Yet, outsiders often misread the Berom. Some call them mere farmers, forgetting the smiths, hunters, and artists they have always been. Others assume Christianity erased their culture, when the sight of thousands dancing each April tells another story. Conflict has sometimes painted them as hostile, but their history of intermarriage and exchange suggests the opposite. Think again of your Berom friends: how much of their story do you know? And how much of what you “know” is only stereotype?

The Berom Today

Today, the Berom walk in two worlds. They speak English and Hausa, yet sing in Berom. They worship in churches, yet dance the same steps their ancestors once did. Their children excel in politics, sports, and academia, but still return home each April to the festival ground, where the air fills with drums, color, and memory. To see them is to realize that culture can bend without breaking.

Lessons Born From Heritage

The Berom story is proof that identity is not fragile it is fire. Sometimes it flickers, sometimes it roars, but it refuses to go out. Their dances carry memory, their names carry history, their leaders carry continuity. For Plateau State, they are cultural anchors. For Nigeria, they are a lesson: that even in the face of disruption, identity can adapt, endure, and still command the stage.