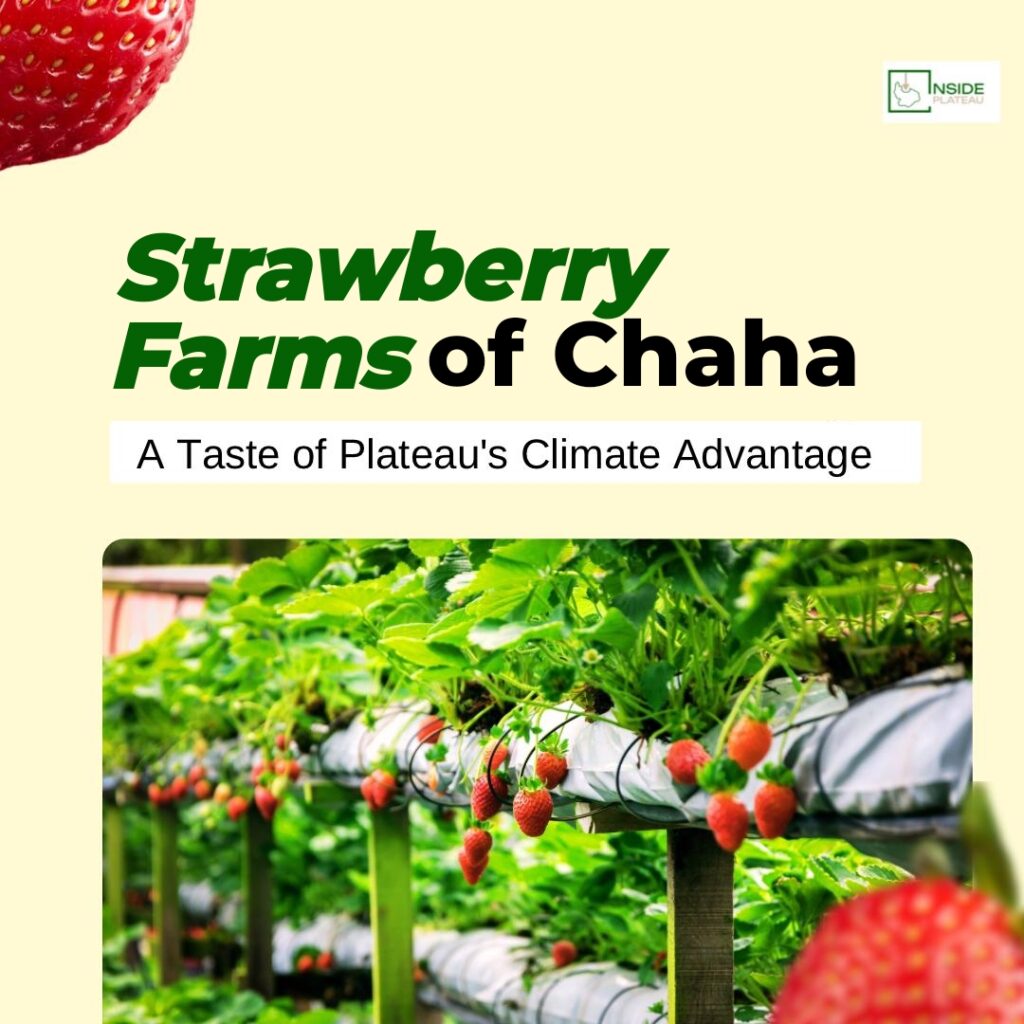

It’s easy to think you’ve seen it all… until the colour hits you. When it’s on television, it looks like little rubies on a plate. But in real life, especially while they are still hanging on their stalk, they appear like little drops of sunset scattered on the soil. Yes, the strawberries in Chaha don’t just grow, they glow! Perhaps, these are in fact one of Plateau State’s greatest wonders.

Each new day, the morning fog sits heavy on the fields, kissing every leaf with dew. It’s why these berries thrive in the rocky highlands they now call home. Nobody quite remembers how they made their way to these parts of the world, but whether they arrived with missionaries or ambitious merchants, strawberries on the Plateau are now as rooted in the people’s heritage and livelihood as their songs and dance.

The Village That Grows Sweetness

Nowhere else in Nigeria are these sumptuous beauties more popular than in Chaha—a small community tucked into the high-altitude folds of Jos South Local Government Area of Plateau State. For decades, this almost-invisible place has been mastering the art of growing strawberries in Nigeria; and in recent times those efforts have proven most successful. So much so that it’s often said that 80-85% of the strawberries consumed across the country are sourced from this village. While no formal study confirms the figure, suppliers and local traders frequently repeat it as common industry wisdom.

“What makes this place so special?” you may ask. Perhaps it’s the climate. While Plateau State is generally cool, here in Chaha, agricultural activity outweighs industrial functions, and the cold isn’t a seasonal guest but a principal authority. This is the kind of place where your breath fogs up before you could say “good morning”; where the mist rolls down the hills like a curtain.

That natural chill, the kind that drives visitors to wrap up, is exactly what strawberries love best. It’s why Chaha became the unlikely cradle of one of Nigeria’s most delicate crops. To the people, the fine weather doesn’t signal vacation but harvest.

Here, the soil is dark and generous, the sun polite, and the people ingenious. Over the years, families have turned this cool corner of Plateau State into an orchard of opportunity; proving that red gold can indeed grow in green hills.

The People Behind the Berries

The magic of Chaha’s strawberries goes beyond the taste, feel, and beauty of the fruit. On the contrary, its power lies in the people who coax them from the earth. Despite little or no formal agricultural training, ordinary individuals have mastered the rhythm of the soil by touch and tradition.

Another feature that keeps this community alive and thriving is their spirit of trust and collaboration. Among the average Chaha farmer, partnerships are as common as the berries themselves. One person may bring land (often ancestral), another capital, seedlings and technical know-how. Together, they share risk, harvest and reward.

One farmer we met, a woman from the Bassa, tends a thriving strawberry field on a piece of land owned by a local Berom family in the area. While she brings the money and the mastery, he brings the soil and the history. It’s a partnership rooted in trust and mutual gain; the kind of quiet collaboration that sustains the heart of rural Plateau.

Similarly, these partnerships extend to a system of cooperative farming or labour-exchange often referred to as “gaya”. In this case, the farmers (usually family members) support each other with free labour that is reciprocated when the other needs help. If one farmer has a large portion to cultivate but lacks enough hands or funds, they invite relatives to assist and repay with their own time when the other calls on them.

The Code of Loyalty

If you ever plan to buy strawberries directly from Chaha, here is your first lesson: don’t go in alone. The reason may not be as commercial as it sounds but, aside from partnerships, these local farmers thrive on loyalty.

Chaha is not your regular “come-and-buy” village market. Strawberry trading here runs on something deeper than money: it runs on relationships. The strawberry farmers have long-standing links with their buyers, many of whom have stood by them through thin harvests and good years. So walking in with cash in hand doesn’t guarantee a sale. You’ll need an introduction, a handshake, maybe even a cup of bwirik (the local beverage made from millet or sorghum).

Over the last few decades, Chaha has grown beyond a community into an ecosystem; and in ecosystems, trust is the fertilizer that makes things grow.

The Art and Science of Growing Strawberries

Despite how fragile they look, strawberries are not easy to grow. They need patience, precision and the right kind of stubbornness.

They are planted in June when the rains are steady. The farmers invest in tilling the ground, weeding the ridges and, in the dry season, watering the stalks so they can stay alive. The stalks, however, need little water to survive the dry spell (from October until the next rains begin). Their roots are watered through drip irrigation, not sprinklers, because too much water can drown the roots or spoil the fruit. Each drop counts, delivered slow and steady through plastic pipes that snake across the beds like lifelines.

To keep the fruit clean and unsoiled, rice chaff is laced around each ridge or bed. This ensures the berries have minimal contact with dusty or muddy ground.

In addition to cultivation, fertilizer is measured as much as water. Too much fertilizer and the fruit grows big but loses sweetness; too little and the yield drops. It’s a delicate balance; one that only experience can teach.

And when the rains return the next year, strawberry season takes a break. The fruit hates being drenched: its time to shine is after the rains, when the air is dry and the land is cool again.

The Quiet Business Waiting to Bloom

Despite its picky nature, strawberry production is among the most lucrative agricultural businesses on the Plateau. On a good day, harvests range from 20-200 cartons (each weighing about 5.5 kg, depending on farm size). Each carton currently sells for about ₦18-20 thousand. And the best part is: through the dry season, the farm keeps producing more and more strawberries every 1-2 days.

While the business of farming is attractive, there’s one thing that could make this “red gold” shine brighter — and that is packaging. Presently, most Chaha farmers sell their strawberries in generic cartons (often recycled Maggi boxes rescued from shop floors), with the price of each running between ₦150 and ₦250.

Before they are used, holes are bored into the sides to create ventilation, allowing the berries to breathe during transport. Without ventilation the delicate fruits would sweat and spoil long before reaching their destination.

But these cartons don’t return once they leave; they’re single-use lifelines. This is why farmers often stock in bulk. As one farmer explained, she buys up to 500 cartons at a time, not because she needs them all immediately, but because “everyone is chasing cartons” and you never know when the market will run dry.

It’s an odd irony that what many discard elsewhere becomes one of Chaha’s most sought-after tools. Here, even a second-hand Maggi box holds value because inside it travels the red gold of the Plateau. A purchase of purpose-built, temperature-friendly boxes could change everything from protecting the fruit, to extending its life, and allowing farmers to own a distinct identity in the market.

Some have whispered that custom-made cartons might be too expensive. But, imagine if a local entrepreneur took up that challenge: producing affordable, branded packaging right here on the Plateau. It wouldn’t just be packaging; it would be pride. Strawberry from Chaha should say so boldly on the box: “grown in the cold heart of Nigeria.”

Finally, on shelf life: the delicate nature of strawberries means that without cold-chain or proper packaging the fruit seldom lasts more than a few days at ambient temperature. Studies show that with low-temperature storage (around 4 °C) and modified atmosphere packaging, shelf life may extend to between 5-15 days depending on cultivar and conditions. Packaging investment and basic cold-chain infrastructure in Chaha could therefore significantly reduce wastage and raise value for producers.

The Sweet Revolution

Strawberries may not be oil or tin or gold, but in Chaha, they’re proof that beauty can be grown, not mined. They remind us that Plateau’s strength isn’t buried beneath the rocks but alive in its people, its soil, and its stubborn, stunning cold.

“The land brings the berries, but its our hands that bring them to life,” says one of the farmers in Chaha. And in all sincerity, it is true. Perhaps strawberries are rampant here not because the land chose to bring them into existence but because the people dared to grow something different, something strange and new.

So next time you see a basket of strawberries (red, glossy and fragrant) know that behind that sweetness lies a story of courage, community and cold mornings in Chaha. And if you ever make it there, don’t forget your jacket. Cause, while the strawberries won’t shiver in your hands, you just might.