Roots in the Soil

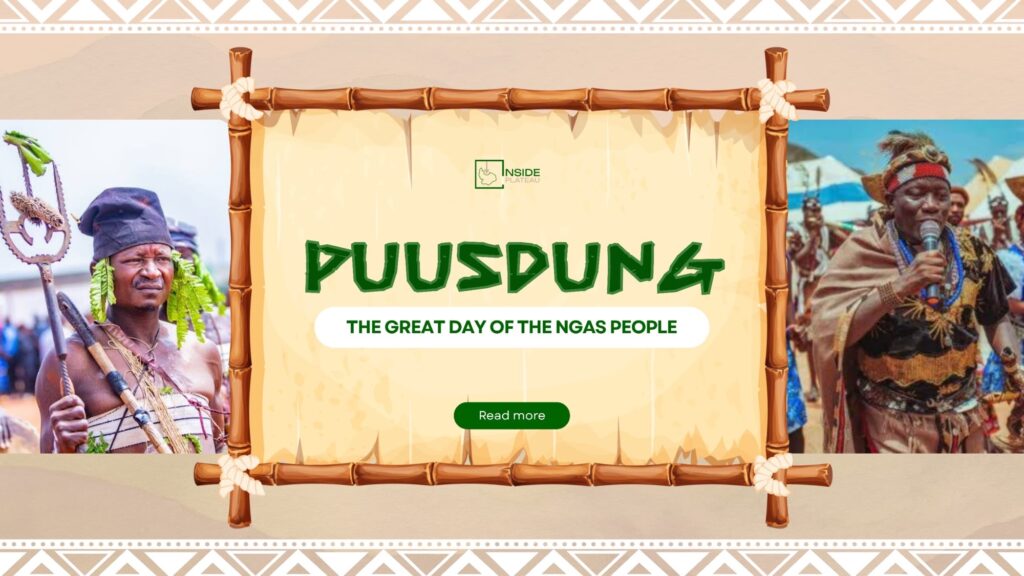

Each April, the Ngas people of Plateau State gather for Puusdung the “Great Day” a festival where memory, music, and identity collide. What began as a farmer’s thanksgiving has become a living archive of culture, carried forward not by inheritance alone but by the active embrace of every new generation.

It was in 1988 that the Ngas Youth Movement envisioned a unifying day for their people and brought Puusdung to life. Once a simple one-day thanksgiving, it has grown into a cultural institution, shaping the rhythm of Ngas life for nearly four decades.

Today, Puusdung is no longer confined to a single day. It has blossomed into a week-long fiesta of activities economic roundtables, gala nights, and cultural displays before climaxing in a spectacle of dance, masquerade, and music. Each year brings with it a theme that reflects the current heartbeat of the people, with recent editions focusing on education, development, and the empowerment of youth. This shows how tradition is never static; it evolves, stretches, and speaks to the needs of the present.

Between Past and Possibility

That balance between the old and the new is what gives Puusdung its enduring power. While it remains rooted in cultural pride, it also engages with modern realities. Festivals now double as opportunities for dialogue—about education, infrastructure, and the future of Ngas land. Far from being a relic of the past, Puusdung is proof that tradition can be both a compass and a conversation.

At the Pankshin Mini Stadium this April, where thousands gathered for Puusdung 2025, it was this shared value that stirred the heart. The songs may now be amplified by loudspeakers, the dancers may march on modern turf, but the essence remains unchanged.

Today, the Ngas are no longer only farmers and artisans. They are professors, politicians, engineers, and entrepreneurs. Their markets stretch beyond Plateau, into other parts of Nigeria and the diaspora. Yet, in every stride of modernization, Puusdung becomes the pause that reminds them: “This is where you began.”

Governor Caleb Mutfwang, addressing the sea of celebrants in Pankshin, voiced this need for cultural continuity with striking clarity:

“As a government, we are determined to promote our cultural heritage as part of our tourism and development agenda. However, I appeal that cultural celebrations be kept free from partisan politics,” he urged.

His words, delivered under the Plateau sun, were less about policy and more about identity. In a state that has seen its share of conflict, Puusdung’s drumbeats seemed to echo his call for unity louder than any campaign speech could.

It was as if the festival became a communal hearth, drawing leaders and citizens to warm themselves at the same fire of shared heritage.

In one corner, a father leans close to his son, explaining the meaning of the masquerade that dances before them. The boy listens wide-eyed, caught between awe and curiosity, his small fingers gripping his father’s hand. In this exchange, knowledge passes quietly, intimately. Tradition lives not in museums, but in the charged space between generations.

Custodians of Culture

Nearby, a group of teenage girls adjust their headscarves before joining the dance. Their laughter is light, unforced, carrying the thrill of participation. They do not appear burdened by obligation, nor coerced into performance. Rather, they step eagerly, their movements syncing with the drummers’ pulse, their faces radiant with ownership of the moment.

This is how Puusdung endures. Each generation does more than inherit itthey reinvent it. For some, that means remixing old songs for TikTok or sharing snapshots on Instagram; for others, it means committing to themes like education and youth development that have recently guided the festival’s direction. In both cases, the message is clear: the culture is alive because the young claim it as their own.

Part of Puusdung’s magic lies in its ability to draw both locals and visitors. Tourists marvel at the artistry of masquerades, the swirl of colours, the aroma of freshly pounded yam and spiced stews drifting through the air. But for the Ngas, it is more than a show. It is a mirror reflecting who they are, a reminder that culture is not an ornament to be polished once a year but the daily fabric of their being.

And so, when the music fades and the costumes are packed away, what remains is not nostalgia but renewal. The festival is not simply a revival of what was but a re-affirmation of what still is. From the youth who conceived it in 1988 to the children who now dance in its heart, Puusdung is proof that traditions thrive when each generation participates fully, joyfully, and deliberately.

Puusdung, the Living Heritage

The beauty of Puusdung lies in its dual character. On one hand, it is ancient, grounded in the rhythms of farming cycles, the clang of blacksmiths’ tools, and the vibrant hum of market life that once defined the Ngas economy. On the other, it is dynamic embracing contemporary realities, hosting state dignitaries, and serving as a platform for tourism and development.

In that tension between past and present, Puusdung becomes more than heritage it becomes a living archive, a reminder that cultures survive not by freezing in time but by adapting without losing their essence.

If farming was the old theatre of Ngas identity, Puusdung is the modern stage. Its dancers twirl not only for entertainment but as symbols of survival. The drummers summon not just rhythm but memory. Every costume a fusion of woven textures, beads, and colours carries echoes of blacksmith anvils and pottery wheels.

One could say Puusdung is where the past wears modern shoes. It is as much about ancestral rituals as it is about today’s aspirations. For instance, when Hon. Yusuf Gagdi announced his ₦15 million donation to support the festival and pledged clean water for his constituency, it was a reminder that even development promises find resonance in cultural gatherings. What better place to announce a vision for tomorrow than before the very people whose heritage holds the lessons of yesterday?

Festivals like Rio’s Carnival, Japan’s Hanami, or New Orleans’ Mardi Gras show how cultures turn tradition into identity on a global stage. Puusdung, though smaller, belongs in this company: a festival that tells the world that the Ngas people, too, have a rhythm worth hearing.

The Dance Continues

Puusdung is more than Plateau’s cultural showpiece; it is a declaration. It declares that heritage is not fragile, not something to be mourned or preserved behind glass. It is resilient, adaptive, and alive. For the Ngas, celebrating Puusdung each year is both remembrance and resistance: a way of saying, we are here, and we remain ourselves.

In this way, the Great Day is not just a cultural festival but a living covenant between past and present. As long as the drums of Puusdung sound, the Great Day will remain more than an event. It will remain a rhythm, steady as the heartbeat of the Plateau, reminding every Ngas child and every guest that heritage is not behind us it is alive beneath our feet.