A Face That Speaks Before Words

Among the Ngas people of Plateau State, Nigeria, appearance is not vanity it is vocabulary. The very word Ngas means “cheek”, a reminder that identity begins on the face. To meet an Ngas elder was, in earlier times, to read a story etched in flesh. With the bak chal or linzami, a bold tribal mark drawn from above the ear down to the jawline, children carried their heritage permanently inscribed.

Later, softer adornments known as mbi yit me or mbi gyer (two neat marks beneath the eyes or near the nostrils) emerged, no longer only symbols of identity but of beauty and self-expression. These marks functioned like jewelry of the skin, proof that even before the first garment is tied, the body itself is dressed in culture.

Draped in Banne, Clothed in History

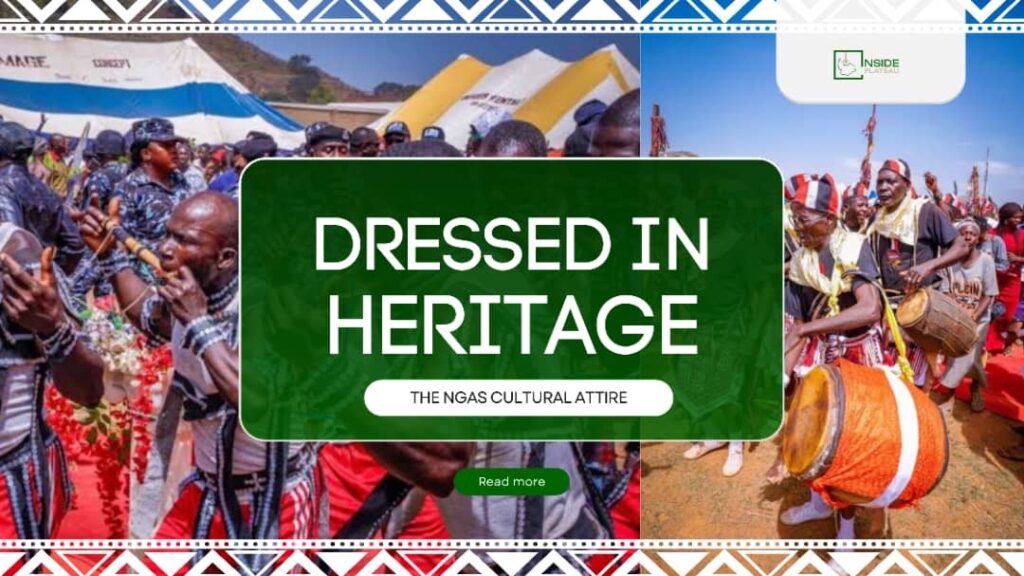

If the face spoke identity, the body answered with fabric. For Ngas men, the banne was more than attire; it was a rite of passage. After the sacred initiation of vwang, when boys were circumcised and groomed into adulthood, the incorporation festival followed, and there, banne appeared. It was not just clothing but a cloak of maturity, a declaration that childhood had ended and responsibility had begun.

Traditionally, banne was made from animal skins or handwoven cloth, dyed in earthy tones that mirrored the Plateau landscape. It was wrapped around the body or slung across the shoulder with quiet pride. With banne came pas (spears), beads, and sometimes skins of wild animals worn as cloaks. Together, they transformed a youth into a man, draped not only in cloth but in courage, resilience, and duty.

The Color and Grace of Womanhood

While men wore banne as the banner of adulthood, Ngas women clothed themselves in grace designed for daily life. Known as homemakers, they fetched water in clay pots called tul, carried bundles of firewood from the hills, and tended to farms and families. Their attire reflected this rhythm practical yet adorned. Beads shimmered against the sunlight, cowries rattled softly with each step, and woven wrappers balanced modesty with elegance.

Here, beauty was not extravagant but purposeful. The clothes did not weigh them down, they moved with their tasks, as much a part of home and hearth as the tul balanced perfectly on their heads.

Dressing as Belonging

In Ngas culture, identity was never only about appearance; it was also about personhood. A true Ngas (nkarang) was known for bravery, integrity, and responsibility. Failure to embody these virtues made one an nlap (an outsider) no matter his birth. Yet clothing played its role in this invisible test.

To wear banne with dignity, to knot a wrapper properly at a festival, to adorn oneself with beads that spoke of family and heritage, these were not just fashion statements. They were visible proofs of belonging. They were the fabric version of values, a textile oath that said, “I am Ngas, and I carry my people with me.”

Wealth in the Everyday

What is striking about the Ngas cultural attire is not only the artistry but the philosophy. Plateau is a land rich in minerals gems, stones, and metals that could adorn kings and chiefs. Yet the Ngas, like many Plateau cultures, chose otherwise. They turned to nature’s simple gifts pods, skins, feathers, leaves.

This choice speaks loudly: wealth is not what lies hidden underground, but what grows around you, alive and abundant. To wear the earth itself is to declare belonging, humility, and pride all at once.

Dancing Between Tradition and Change

Time, as always, has tugged at tradition. With colonial contact and modern trade, imported fabrics like George, Lace, and Ankara slipped into Ngas wardrobes. Today, it is common to see banne-inspired wrappers sewn into modern shirts, trousers, or dresses. In some weddings, brides wrap themselves in Ankara while still adorning their waists with beads of their grandmothers’ style. Grooms might combine a western suit with the unmistakable drape of banne fabric, creating an attire that is both past and present.

Yet this is not a bending of culture but an enrichment of it. Modernity has not replaced Ngas tradition it has layered it. The old banne lives on in rites of passage and festivals, while its essence flows into new forms, reminding us that culture, like cloth, can be rewoven without losing its threads.

Heritage in Hues

If the weaving of attire holds the body, the weaving of color speaks to the soul. In earlier times, Ngas men and women clothed themselves in leaves, skins, and beads. Today, with the coming of woven and imported fabrics, colors now carry the cultural weight once borne by natural materials. These hues are not random decoration but deliberate symbols, tying past to present.

White (Zum or Tongzum) embodies peace, reflecting the accommodating heart of the Ngas. Blue (Kop) conveys royalty and dignity, affirming that every person is respected. Deep blue or black (Yil rit) speaks of fertility and productivity, echoing the richness of both land and labor. And red (Bud fi) burns with bravery quiet in peace, fierce in defense, a warning to intruders that the Ngas will guard their home.

Woven into fabric, whether handspun on local looms or cut from imported cloth, these colors have become more than attire. They are the living palette of Ngas identity: what was, what is, and what is to come. A testament to the fluidity of culture, they remind us that tradition does not vanish with change it adapts, carrying its essence forward in new forms.

Where the Past Walks with the Present

To watch an Ngas festival, today, is to see time braided together. One man may stand tall in banne, wrapped as his forefathers were. Beside him, a woman in Ankara patterned with bright dyes carries a tul-shaped accessory to honor her roots. Dancers move in circles, their faces glowing with modern joy, their cheeks carrying the memory of bak chal or the gentle echo of mbi yit me, and their legs wrapped with rattles made from hollow pods of plants concealing tiny shells.

Attire, here, is no ornament. It is a language fluid, evolving, and resilient. It is identity stitched in fabric, carved in skin, strung in beads, and carried in every tul, every banne, every pas. To dress Ngas is to speak Ngas; to speak Ngas is to be Ngas. Because in the end, attire is the language of identity. And through cloth, beads, skins, and feathers, the Ngas people continue to speak—strong, alive, unbroken.